Lerab Ling, 4 August 2003

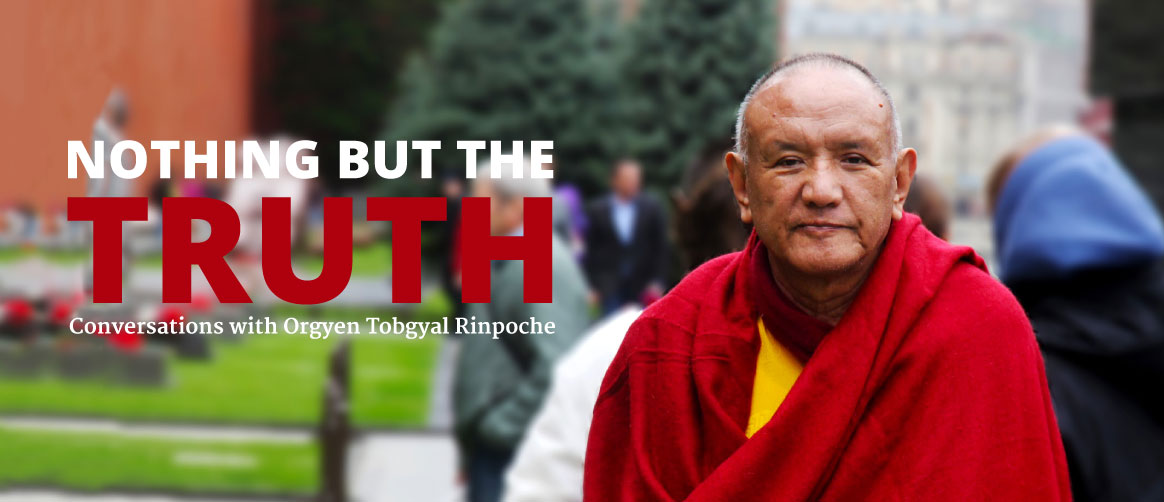

Late one evening, in the old stone building in Lerab Ling that had been transformed, almost magically, into a Tibetan shrine, Orgyen Tobgyal Rinpoche gave Rigpa students some advice about how to perform ceremonies. He felt compelled to do this after he witnessed, towards the end of a drupchen, one of the nuns spilling a cup of hot tea all over Sogyal Rinpoche, in full ceremonial regalia. Sadly, none of the translators that day could satisfy Rinpoche, so this is one of the very rare talks Orgyen Tobgyal Rinpoche has given in English “…because it’s not a teaching, it’s not about Dharma, it’s just about Tibetan traditions” – and the importance of making haste slowly.

This isn’t a ‘teaching’, it’s about the traditional way of doing things in a Dharma situation. We’re going to look at how our work and activities accord with the Dharma. Of course, someone who just practices alone, a more self-contained kind of practitioner, won’t need to apply these kinds of tradition, because they can do whatever they want. But once a group of four or more monks start living together – what we call a 'sangha' – they must follow the teachings Buddha himself gave in the Vinaya about all the activities they should accomplish as a community.

1. Be Careful: Think Before You Speak or Act

Right now there are a lot of us here in Lerab Ling for this drupchen. As we perform Dharma ceremonies together, we must always follow the authentic tradition. When we take part in anything to do the Dharma, it’s essential to be both aware and careful. If you are always aware and work carefully, whatever you do will turn out well. But if you are inattentive and restless, everything you do will bear the mark of carelessness. Therefore, first and foremost, you must be careful and aware.

So, how do you learn to be careful? You start by thinking through the task you must complete before you act. Think over what it is you need to do. If you don't think first, your hand won’t be able to do anything, right? You must think with the mind before your body can act. To act impulsively the moment a thought arises, is not being careful. Always allow the thought to settle before you act. Pause and consider what needs to be done. Only then will you be able to act carefully.

Imagine the thought, “I must pour some tea into the lama's cup” arises in your mind. In that very instant you rush over to the lama and pour the tea. But you don’t do it carefully. So now imagine that instead of acting impulsively, you think about how you are going to pour the tea before you make a move.

- How will you hold the teapot?

- How will you remove the lid of the lama’s cup, remembering it could break if it falls?

- How will you stand? If you’re body shakes because you’re standing awkwardly, it’s easy to spill a full cup of tea.

- If the lama’s table is full, where will you put the cup?

If you’ve thought about all this before actually doing it, you’ll be able to place the cup in the right position on the table with sure hands. This is what being careful means; this is ‘carefulness’.

If you try to do anything while thinking about something else, you are not being careful. If, while you pour the tea, you think about what else needs to be done, you will spill the tea – you are not being careful. So whatever you do, must be done carefully.

This also applies to speaking. If you think about what it is you want to say before you open your mouth, you will communicate well. But if you don’t think before you speak and just blabber ‘spontaneously’, you won’t have a clue what you’re talking about. For example, I want to talk to Philip, but haven’t thought about what I want to tell him. So I go up to him and say, “Hi Phillip...” but have nothing else to say. “Hi Phillip...” on it’s own doesn’t say anything at all! So, you must be careful.

All you red-headed[1]When the English first arrived in Lhasa, to the Tibetans it looked as if they all had red hair, so foreigners became the ‘red-headed’ ones; similarly lay Tibetans were called ‘black-headed’ ones, because they had hair and monks didn’t. people act carelessly most of the time. You’re rough and imprecise. If a lama calls for you, you instantly start rushing around. But all that happens is you get into a real tizzy. Then if someone asks you what the lama told you to do, you don't know. That's one example, but I've seen it happen often.

Maybe there are lamas who like that kind of behaviour, who think such people are good attendants. But they don’t think, they just do whatever the lama tells them to – like computers. A computer has no thoughts or opinions of its own, it’s a slave to its programming. Which might be a good quality in an attendant, but not when that attendant acts carelessly. Can you answer the question, “Why are you doing what you’re doing?” If I myself don't know what I’m doing, then how can I do it? This point about being careful throughout all your activities is a very important one.

2. Don’t Rush!

Now my second point is that any work or activity done in a temple or a monastic environment must be done peacefully by someone whose mind has been tamed. Let’s say your task is to put a glass on the table. To drop it onto the table too quickly is inappropriate and anyway it looks bad. So it’s best to place the glass calmly and deliberately. During a ceremony, especially when there’s a large crowd of people participating, even if you’re very, very busy and in a real hurry, it’s better to walk everywhere slowly. Running looks very bad. But it happened a lot the other day. People were running backwards and forwards and up and down the aisle of the temple hysterically, and they constantly bumped into each other. Even the chöpons we brought from India, who aren’t very experienced or that good, were really flustered. An experienced chöpon knows exactly what will be needed during a ceremony and prepares everything beforehand. They are then able to do whatever’s necessary at the right time, carefully and without panic. If you aren’t prepared, when someone says, “We need some rice!” you'll then have to chase around to find some rice. If you’re asked for water, you’ll have to rush to get some. If you’re asked for fire, you’ll have to light a fire. This is how the kind of pandemonium you had when the cup was spilt is created, with people running in circles and knocking things over. Do things slowly! Even if you’re mind is full and really busy, don’t let that busy-ness out! Don’t let your state of mind affect how you behave. Even when there’s a lot to be done, do it calmly.

If you don’t maintain self-control, your state of mind will make you red in the face, you’ll start shaking and all sorts of similar inconvenient symptoms will advertise your state of mind to all and sundry – this is bad. If you panic inside it shows in your eyes – you blink a lot and your gaze darts all over the place. When you get in a state like that, you can’t hear what’s said to you because your consciousness is somewhere else – you've spaced out. So you should do everything very peacefully and very gently. The busier you get physically, the calmer and more deliberate you should become. Then you won’t drop what you’re supposed to be offering. Or wear your hat the wrong way round. Or pick up a vase of flowers when you’re supposed to be ringing your bell. These things really happen! I’ve seen it with my own eyes! When you get worked up you can never find the right page in the text. As you leaf through your practice, everything looks jumbled up, and all that feverish shuffling only adds to your confusion. So however quick you want to be, however much there is to do, be relaxed about it. Acting instantly on a thought without preparing properly can’t ever be described as ‘beneficial’. That's my second point.

3. Hierarchy: Ceremonial Roles

If a ceremony is to be done well, you need more than one person to organize and perform it. Several people must work together, some taking roles in the practice itself, others to serve. When you’re on your own you don’t need a servant or any kind of help in order to drink a glass of water. But in the context of a ceremony, someone is needed to serve water to the master. In fact you need quite a lot of people just to serve the lamas and practitioners. Several levels of participation are required in order to perform a ‘ceremony’. During the drupchens the other day, Sogyal Rinpoche assumed the highest level, and the four people to his right and left undertook the second level. Most of the rest of you participated at the ordinary level. People who prepare and serve tea also fall into different categories. In a ceremony, it would be very bad for Sogyal Rinpoche to have to get up and pour his own tea; it wouldn't be a good ceremony. But that’s what would happen if you didn’t have these different levels of participation and service.

If you don’t prepare everything in advance, then instructions must be given on the spot. And that means a lot of shouting in the temple to tell people what to do. For example yesterday, Sogyal Rinpoche had to write many notes and send them to people in different parts of Lerab Ling to summon them to the ceremony. There was also a great deal of whispering in ears – but many of you seemed to be deaf. All this disturbed the ceremony. Ceremonies should be conducted in an atmosphere that’s calm, like a great lake of tranquility, in which anything that needs doing happens quite naturally.

To do a ceremony successfully, it is crucial for all the different levels of participation to be covered, so there are people who take the highest level, the secondary level, the third level, and so on. Of this there is no doubt. And if you don't organize a ceremony in this way, it’ll turn out very badly. Do you understand?

I am not familiar with European traditions and I don't think I’ve ever seen a European ceremony. But based on what I have seen, the Japanese do ceremonies best of all. Every aspect is held with the greatest care. The Tibetan tradition is also good, but these days it’s not upheld that well. Even the ceremonies held at the Dalai Lama’s residence have lost the lustre they used to have. Of the ceremonies organized in monasteries, those held around the previous Karmapa used to be exceedingly majestic. They were done very well. But these days that’s also been lost!

There are many different traditions of doing ceremonies in this world, but as we are concerned with the Dharma and follow the teachings of Tibetan Buddhism, our ceremonies follow the Tibetan tradition. There are many ceremonies in the Christian tradition too, aren’t there? But we follow Tibetan way of doing things, which is a little difficult for Europeans and foreigners to follow. But even though it’s difficult, you have to do it.

First of all, as you perform the ceremony you must display great respect. So, for example if you serve tea to the lamas, you must carry the tea and the cups very high – this is the Tibetan tradition. Everyone must also offer kataks. This is also a Tibetan tradition, isn’t it? We often see you Rigpa people lined up along the path holding kataks. Some Tibetans find it quite humorous. “They are copying our tradition! How weird is that?” In America I saw some students offer kataks by holding them in front of their heads, bending over slightly, then after a while putting the katak around their necks themselves! They seemed to think the tradition was about wearing a katak, and thought it was OK to put it on themselves. But in Tibet there is absolutely no tradition of doing it that way. A katak is something you offer to another person, you never put it on yourself.

There are many things like that. According to Tibetan tradition, there is a difference between the kind of person who serves tea to a monk and to a lay person; monks are served by monks, and lay people by lay people. But what I’m talking about today is how monks and nuns serve tea.

If you could put an empty cup on Sogyal Rinpoche’s table before he even arrived, this nun wouldn’t have been able to drop his cup. But that isn’t allowed in the Tibetan tradition. In the west, when you go to a formal dinner party, the table has been laid before you sit down to eat. But according to Tibetan tradition we can’t do that. The table must have nothing on it when the important guests arrive. Once they’ve taken their seats, a saucer and empty teacup will be brought in by two different servers and placed on their table. The lid of the teacup will then be lifted, while somebody else pours the tea.

Actually strictly speaking, when really important guests, like the Dalai Lama, are present there’s another stage to offering tea. If we had a big ceremony at my monastery, like the one we had here yesterday at Lerab Ling, I would have been sitting at the front in the central aisle. When the tea was brought in, I would have taken my own small cup from my pocket and, witnessed by everyone in the temple, I would have tasted a little of the guest’s tea, to prove it wasn’t poisoned. Only then would the tea server have proceeded to the throne and served the important guest. We’ve never done it here, but that’s how it’s done in our tradition.

Anyway, first you serve the tea, then the rice – rice must not be offered first! The tea is poured into a cup on the table to the left of the guest, and the rice is placed on his right. You should neither put the tea on the right and rice on the left, or put them both together on the same side.

Now, about the lay people who participate. During ceremonies ordinary lay Tibetans are served tea by other Tibetan laypeople. Those serving wear their best hats and a chuba with a brocade shirt underneath. To show off the richness of the brocade shirt, a Tibetan will only wear one sleeve of the chuba, throwing the empty sleeve over his shoulder so that the brocade of the shirt can be seen by everyone. If he puts both his arms into the sleeves of his chuba, his shirt could not be seen. The right sleeve is thrown over his right shoulder, because to leave it hanging casually would be disrespectful.

The tea must be brought into the temple covered with a piece of brocade. The tea-bearers must stop at the top of the aisle and not serve the VIP guests themselves. Actually each lama has one solpön, who is the personal attendant responsible for serving the lama’s food, and he should stand behind the lama, in the same way Ane-la stood behind Sogyal Rinpoche yesterday. The solpön walks to where the tea-bearer stands near the entrance to the temple, removes the brocade cover and throws it over his shoulder. He then takes the tea to the lama, offers it, then brings the pot back to the tea-bearer who takes it out of the temple. The rice is offered in a similar way. The rice-bearer brings rice into the temple, waits inside the door for the solpön to collect the rice, then take it down the aisle to the guest sitting on the throne.

Nowadays lamas, or monks, or even nuns – actually I don't know if nuns would do this; we didn't have any in Tibet who did. Anyway, lamas or monks drape their zen around their neck from left to right (not right to left), and then hold it between their teeth to cover their mouths, so they don’t breathe over the tea as they pour it.

Those serving tea must never touch the lama himself, or his hat or other personal belongings, with their bare skin, they should cover their hands with a katak first. Yesterday, Rinpoche’s attendant took his hat in her bare hands. Nobody must touch the hat! It is carried in a box, which is opened facing the lama, who takes the hat in his own hands and puts it on his head himself. And when he takes it off, he returns it to the box and covers it with the cloth himself. Sometimes at this point in the ceremony, he may hold the hat up before putting it back in the box. But he does everything himself! No one else can touch the hat. In Tibet, if someone were to touch it, everyone present would be shocked and exclaim, "Arghhh!!!" This is the tradition.

Yesterday Sogyal Rinpoche asked for his Guru Rinpoche hat, someone touched it and confusion ensued. And the box was put on the throne behind Sogyal Rinpoche instead of taken out of the temple.

In the Tibetan tradition attendants are monks and always wear zen and shamtap. When serving a high lama like the Dalai Lama, the solpön should wear a yellow mask over his mouth, not a katak. If the lama isn’t that high the mask should be white. The Chinese and the Tibetans share the same tradition of yellow being the colour that denotes a high status. So in this case, the solpön should wear a white mask to cover his mouth. But no one else should.

Traditionally there are thirteen kinds of attendant. The first three must be monks.

- The ‘solpön’, a monk who serves all the lama’s food, drink, tea etc., and looks after the lama's cup and eating utensils, etc.

- The ‘zimpön’, a monk who is responsible for making the lama’s bed, putting him to bed at night, taking care of his clothes, etc. – everything to do with the lama’s sleep and clothing.

- The 'chöpon', a monk who arranges the shrine, and so on, makes tormas, and cares for everything the lama needs for pujas – bell and dorje, pumbha, etc.

- The 'chakdzö' is the general secretary, sometimes called a bursar, or treasurer, who can either be a layman or a lama or a monk.

- The 'nyerpa' is in charge of the kitchen, but he’s not the cook, he’s the manager. He decides on lunch and dinner menus, then checks them with the lama and orders all the food.

- The 'machen’ is the cook. He will cook whatever the nyerpa tells him to. During a large ceremony, it is the machen who brings the tea to the entrance of the temple. Actually the job of the machen is crucial because he very publicly takes tea that he has prepared himself, all the way from the stove to the temple, and by doing so prevents anyone else from poisoning it. No one else can be sent to fetch the tea, nor can the machen send the tea with anyone else. Even if he’s really busy, the machen must take it to the temple himself.

- & 8. The 'drung-nyer' are in charge of the lama’s schedule and are usually the ones who pass messages to him, make requests or ask questions. There must be two drung-nyer in a lama’s entourage, so that if one of them is arranging a meeting, the other can remain with the lama to pass on people’s requests and questions and messages. One drung-nyer must always be with the lama.

An important point to remember during ceremonies is that if something crucial needs to be said to the lama, you can’t just stand up and talk spontaneously. First you call the drung-nyer and talk to him. Then the drung-nyer approaches the lama and passes on the information. If the lama is sent an important letter, it must be given to the drung-nyer, who will pass it to the lama. This tradition applies specifically to people of high status. - The 'gakpa' makes sure that when people enter the room they don’t just sit where they like, he directs them to the right seat. He’s not a bodyguard, he just makes sure everyone sits where they should. But he’s not needed here, in Lerab Ling.[2] There are four more categories of those who serve high lamas, but Rinpoche didn’t mention them during this teaching as they do not have a role during the ceremony. “The thirteen officials consisted of the food attendant, the clothing attendant, ceremonial attendant, receptionist, secretary, treasurer, the kitchen attendant, the courier, the furniture attendant, gardener, and the caretakers of the horses, dzo, and dogs.” Shakabpa, Tsepon Wangchuk Deden. One Hundred Thousand Moons: An Advanced Political History of Tibet. BRILL, 2009, n.45 p.241.

These are the categories of people who are traditionally required to serve high lamas. The tradition was initiated by the great Sakyapa master Drogön Chögyal Pakpa, who was the first lama to emerge as a political leader in Tibet. He was also the Khan’s personal priest. Those who came after him, for example the Great Fifth Dalai Lama and Panchen Rinpoche, followed in his footsteps.

4. Ceremonial Protocol: When to Stand Up

Now, how do we behave during a ceremony? When the most important lama walks into the temple, everyone must stand up. But you only stand for the highest lama. Otherwise, if both the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama were at a ceremony, once everyone had stood for the Panchen Lama, there would be nothing left for them to do when the Dalai Lama arrived, right? So everyone must remain seated until the most important person arrives.

What you do here at Lerab Ling is, you stand, bow slightly and fold your hands, but I don’t know what that’s all about. We Tibetans don’t usually do that, but westerners do. You stand with your back slightly bent and you look up with your hands folded in front of your face...

During yesterday’s ceremony Sogyal Rinpoche was the highest lama and so everyone stood up when he walked in. If everybody were to get up each time any Rinpoche walked in, it wouldn’t be special for them to stand for Sogyal Rinpoche. At a ceremony with the Dalai Lama, even if Kyabjé Trulshik Rinpoche were to walk in, we Tibetans wouldn’t stand up – we wouldn’t need to! Basically, in such a situation, we don’t get up for anyone other than the Dalai Lama. Only when he arrives will everyone stands up!

5. Ceremonial Protocol: Seating Arrangements

Now the seating arrangements. Everybody should either sit facing the front, or in two rows facing each other across a central aisle. Only one person sits facing the door at the end of the central aisle, and that’s the highest lama. And there are never two ‘highest’ lamas, so there should never be two thrones side by side, facing the door. Here in Lerab Ling we’ve never followed that Tibetan tradition. If the Dalai Lama were at a ceremony with the Karmapa and other very high lamas, according to that tradition, only the Dalai Lama would sit facing down the aisle. All the others, including the Karmapa himself, will sit on either side of the aisle facing each other. The attendants and people the highest lama needs around him, sit behind him on his right and left. But they only sit there so they can take care of the lama. When a lama presides over a big ceremony, he’ll never get off his throne to do things himself, and that’s why he needs at least five attendants to do things for him.

6. Ceremonial Protocol: the Arrival of the Highest Lama

When the highest lama enters the temple in a ceremonial procession, his entourage will walk in with him. At the end of the ceremony, the lama can’t leave by himself, right? It would be entirely inappropriate for his attendants to be scattered all over the temple, chatting with friends while the master left alone. That would be quite bad. So the lama’s entourage enters and leaves with him, in an orderly procession. No attendant or servant should walk out of the building before the lama, except the gakpa whose job it is to clear the path. Everyone else must follow the lama.

When a lama like the Dalai Lama, who holds a very high position, processes into the temple, he must be accompanied by two people, one on his right, one on his left, each holding one of his arms. In the case of the Dalai Lama, one of these people would be the prime minister, and the other would be the Ganden Tripa – in other words a high political leader and a high religious leader. The other time a lama might be accompanied by two people is if the lama is old and has trouble walking, in which case his solpön and zimpön will walk either side of him to give the necessary physical support.

The person who organizes and finances a ceremony will lead the high lama into the temple bearing incense, which is held in a white katak to represent the purity of our minds. Each time we’ve invited the Dalai Lama to our monastery in Bir, I’ve been given the job of bearing the incense. Of course the incense itself is an antidote to bad smells – I’ve heard that bad smells give Sogyal Rinpoche a headache – and also to energize. It seems the Dalai Lama once said, “What is this incense? Who made it? It’s very energizing!”

The incense-bearer could be a layman, but for monastic ceremonies it’s the ‘umze’, or chant master, and the ‘chötrim’, the master of discipline, who walk ahead of the lama waving sticks of incense. The umze and master of discipline are both very important for the ceremony. The umze is most important because he leads the chanting and makes the practice happen. The second most important is the master of discipline who keeps a close eye on the proceedings and makes sure everything is done properly. This is why these two carry incense in the procession. They are followed by two monks playing the gyalings (reed instruments a little like oboes), and the lama, who is accompanied by the parasol holder. The parasol is held over the lama’s head, therefore the lama doesn’t need to wear a hat. These days, though, even in Tibetan monasteries, you’ll see that although he’s walking under a parasol, the lama will wear a yellow hat to protect him from the sun. This is not part of the Tibetan tradition.

7. Planning and Rehearsal

How do we prepare for a ceremony? Let’s say tomorrow we want to hold a big ceremony here in this shrine room. So tonight, you would gather here for a meeting, because the meeting must happen where the ceremony will be held. During the meeting you must rehearse everything that will happen the next day. For example, those involved in the tea service will talk together then rehearse how they will serve the tea. They must decide between themselves who brings it into the temple and who takes it to the lama, etc. The crucial point here is that the rehearsal takes place where the ceremony will happen. If it doesn’t, even if you spend the entire night planning, as soon as you find yourself in the actual ceremony, your references will be entirely different and you won’t know what to do.

During the meeting you should also make a clear plan of who sits where, so that when everyone arrives, they will be able to find their places in an orderly fashion. You should also think about how people enter the temple. It’s important that there’s no rushing around or commotion – yesterday there was far too much! Especially at the back, where there were many children and other sources of agitation. You shouldn’t rush around like that. Why? Even if there are a couple of people sitting at the front wearing suits and ties, if the back of temple is chaotic, then the atmosphere of the ceremony won’t be special. In fact, it looks really bad! Yesterday there were people all over the place, walking up and down, and chatting.... But during a ceremony, you should avoid talking too much! The atmosphere should be very calm. Too much talking makes it more like the clamour of an Indian festival, with all its singing, music and dancing, or shopping at Chandni Chowk, the busiest market in Delhi!

8. Bowls and Cups

The quality of the cup should reflect the status of the guest. The highest lama’s cup, for example, should be of the best quality. A less important lama’s cup should be of a lesser quality. And ordinary people should just have ordinary cups. In some Tibetan monasteries very rich people are given tall cups on high stands. If everyone had a cup like that, the high lama would not be shown the respect that is his due. And only the two or three highest lamas at a ceremony should have gold bowls for their food, not everyone! The next level of lama should be given silver bowls, and everyone else ordinary bowls. At the same time, if three or four lamas get the same kind of gold bowl, they will all have been treated in the same way.

9. Tibetan Ceremonies Must Follow Tibetan Traditions

Don’t mix things up like you did yesterday. If we do a ceremony following Tibetan tradition, tea should be served in Tibetan cups on saucers. Yesterday some people had Tibetan cups while others had a kind of European cup. This is not good. Every aspect of the ceremony should follow one tradition. Mixing European and Tibetan traditions only results in a kind of ‘tukpa’ – a Tibetan soup in which everything, meat, vegetables and other ingredients are mixed together. So you should buy the right cups and bowls, which can then be used for every ceremony.

Why should we do ceremonies according to the Tibetan tradition? Because we follow the Tibetan religion, and the Tibetan religion must be practised according to Tibetan tradition. Imagine what it would like to hold a Tibetan ritual with the decorations and traditions of the Catholic church. It would be terrible! Or what a Catholic priest would look like sitting on a Tibetan throne, wearing a Guru Rinpoche hat, shawl and so on. What do you think? When a Catholic priest sits on a chair like the one the pope sits on, this is very good. But if the Dalai Lama sat on the pope's chair wearing his Buddha Shakyamuni shawl, imagine how bad that would look!

So we must do everything according to Tibetan tradition. Sometimes though, Tibetan traditions came from tertöns or high lamas who say that they had been to the Copper-Coloured Mountain and seen the way Guru Rinpoche did things. But who knows! For example, one of the tunes played on the gyalings was introduced by a tertön who said it was with that tune that Guru Rinpoche welcomed him to the Copper-Coloured Mountain. There are many instances of Dharma and Tibetan tradition being mixed together like this. For myself, I don't know how much truth there is in any of it.

Traditional Carpet

Another important point is that laying a red carpet is a quite common tradition in Tibet, but we don’t have one here in Lerab Ling. A very good quality yellow cloth is sometimes used, with lotuses marking each step.

Sang

Some Tibetans say that the sang or smoke offering is a Bönpo tradition, others that it’s a Chinese tradition. I don't know if either is true. All I know is that Tibetans make smoke offerings. Where the tradition comes from, I don't know. Other aspects of the Tibetan tradition were originally copied from India, but the Indians didn't offer smoke, and sang didn’t come from India.

10. Ceremonies Should be Short

Another important point is that ceremonies should not take too long. If a ceremony takes the whole day, people get bored, fall asleep, or leave. So ceremonies should be short. When you do a big ceremony, the chanting should be short. You must think carefully beforehand about what will be chanted. If you decide on the spur of the moment to chant an extra long-life prayer, or Tara prayers, or Reciting the Names of Manjushri, or The Prayer That Spontaneously Fulfills All Wishes, and go on adding more and more prayers to the ceremony, what’s the result? Some people will chant, others won't, some will fall asleep, others will start chatting, and so on. So think this through beforehand and give the umze a clear, unchangeable list of what will be chanted during the ceremony. Otherwise, if the umze is suddenly told to chant this, that or the other, and everyone adds their favourite practice at the last minute, it won’t be a good ceremony. “Okay, play that tape!” “No, not that one!” “You there, play this instead!” “No, you go and sit there to help him!” This causes a lot of agitation, which is very bad for a ceremony.

11. Enhancing the Splendour

When we perform ceremonies, we do everything we can to make it grand and resplendent. Everybody should sit majestically and you should only ever wear your very best clothes. If you don’t, you won’t be majestic. At a gathering of high, middling and low participants, there must be a sense of grandeur.

So you must think about how grand you want the ceremony to be. If you want it to be big, how big? We can’t do enormously big ceremonies here, but you don’t have to do all the ceremonies the same way all the time. Some will be very big, some smaller. If each time you do a ceremony you do it in exactly the same way, your tradition will become very fixed and inflexible.

For example, every year there’s a welcoming procession in honour of our arrival. People stand in line on both sides of the road holding kataks, as we are driven down to Sogyal Rinpoche's garden where we drink tea. Then we are lead into the temple – which used to be a tent – where we take our usual seats while someone says something before offering kataks. Every year it’s the same routine and we all know what’ll happen next because that’s the way you always do it. Which is good. But you really should vary it a bit depending on the occasion. Every welcoming ceremony shouldn’t be the same. To mark a particular occasion, you should do something new. Some welcomes should be bigger than others. If a high lama comes, he should have a very splendid welcome that exploits all your resources. For other lamas you can do something smaller. For example, just two or three people might offer kataks as the car draws up. If everyone lines up for every lama who comes here, what happens when a really important person comes? How do you make a really special welcome? You can’t! Because you already do everything! There’s nothing left for you to do to make it special anymore. So before a ceremony takes place, you need to think about these things.

For example, you should welcome Chokling Rinpoche fully when he visits Lerab Ling, but when I come, two, three or five people waiting as the car draws up is enough. If everybody who comes here is treated exactly the same way, then there’s no ‘high’ or ‘low’. So right now Rigpa's tradition is that noone is special. In the west when you greet anyone at all, you shake hands, without distinguishing those with a higher status from those with a lower status. But when an extremely important person arrives at Lerab Ling, Sogyal Rinpoche goes all the way up the road to the entrance to greet him, and then escorts him into Lerab Ling personally. For a visitor who isn’t so important, he waits here at the door, and for relatively ordinary visitors, Rinpoche waits in his garden and they are brought to him. Or perhaps Patrick or someone will take the visitor to Sogyal Rinpoche’s room where they sit together and drink tea.

To drink tea and eat sweet rice with guests when they arrive is a Tibetan tradition. Some members of the Tibetan government have to eat five or six different kinds of food during really elaborate welcoming ceremonies! But if it’s a smaller ceremony like the ones we have here, tea and rice is enough. And if the visitor isn’t important you only offer tea, there’s no need for rice. And after the ceremony is over and the guest is about to leave, there’s no need to offer rice. You only offer it when the guest arrives, not when he leaves.

As you plan a ceremony you must consider the status of every participant. Are they considered to be on the highest level, the second level, or the lower level? You can’t arrange a ceremony in the same way you throw a party at your home, when whoever turns up can do as they please. For a ceremony, you must carefully consider each participant.

Actually, you should even study how ceremonies are held. The Dalai Lama said that before he was enthroned, he had to study the enthronement ceremony for three months! Every day, he went to the hall where the enthronement would take place so he could learn what to do. He was told things like: you must sit here, the cabinet ministers will sit there; at this point you must look in that direction, and smile slightly; here you look to your left and smile a little, but don't say anything; now Ganden Tripa (the highest Gelugpa lama), will approach you and you must touch foreheads, then he’ll bow to receive blessings from your hands, which you must give with both hands; when the others come forward, for example the kalön (cabinet minister), bless them with only one hand; and when all the rest come, bless them with the long blessing stick; when tea is served, don’t drink it immediately; the ‘Great Solpön’ will approach bearing a cup, which he holds quite high, and will offer it to you; that’s when you take the cup and saucer; sip the tea, but don’t drink it all, then put the cup down; next the rice will be offered, take a pinch and offer it three times, then eat a little. This is what his ‘Precious Tutor’ and others taught the Dalai Lama over three months.

You must also rehearse for big ceremonies. Everyone must come together to practise how everything will be done on the day. It didn’t used to be so important to rehearse, or should I say not as important as it is now, because there didn’t used to be video cameras. Just two or three hundred people would witness a ceremony, then it was over and done with. But nowadays, everything is videoed and recorded, and once we’re dead, future students will be able to see exactly how we did each ceremony. And they’ll wonder, “What were those people doing?” So rehearsing a ceremony is even more important these days than it used to be.

In a video of one ceremony – an empowerment of Treasury of Kagyü Mantras given by the previous Karmapa at Tulku Urgyen’s monastery – Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche is shown wearing his hat inside out. He was joking with some tulkus – we don’t know exactly who. But you can’t tell from the footage that he was playing around, you just see him putting his hat on inside out and making a face. That video is still played over and over again. Everybody shows that clip now!

When Sakya Dagchen agreed to visit Kham, Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö began the preparations one year beforehand! He studied the ceremonies, worked out what people should wear and ordered new clothes for everyone who’d need them. He also took all the monks to where the welcome ceremony would take place and questioned them about what skills they had.

One day, one monk said, “I know how to play a special tune on the gyaling.”

“What tune?” asked Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö.

Chiké, who was from our monastery, Neten Gön, replied, “It’s called 'Calling the Beautiful Girls'.”

“OK,” said Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö, “Play it now.”

As Chiké played, Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö listened carefully, then said, “Mmm, yes, that was kind of OK.” Then he added, “Now, go down to where Sakya Dagchen will arrive, start playing the tune on your gyaling and walk up here, as you would on the day. I’ll watch how you do it.”

After Chiké had rehearsed walking and playing, Chökyi Lodrö said, “No, no. You’re no good at it, you walk too fast. You must walk slowly while you play the gyaling. Forget it!”

This was how Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö checked how everyone performed their tasks. For example, he noticed a very strong monk and told him to carry the parasol. He then watched him do it and corrected him, “You don’t just hold it, you must turn a little all the time, like this.”

He even checked Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche.

“When Sakya Dagchen arrives we must escort him into the monastery in a grand procession. What do you plan to wear?”

“The clothes I’m wearing,” replied Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche. “They’re all I have. I don’t have any special ceremonial robes.”

“Well, they’re not good enough,” said Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö. “I’ll have some new ones made for you.”

He then called for his secretary, Tsewang Paljor, and told him to make sure a complete new set of clothes were made for Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche.

This is the kind of preparation that big ceremonies require. We must prepare and train ourselves beforehand. If we don't, what do we do? Nothing!

Here we’re discussing the Tibetan tradition. The western tradition is easy. Men wear a suit and tie and women take off most of their cloth and show a lot of flesh.

I went to the Cannes film festival with Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche and Sogyal Rinpoche. We wanted go into a cinema, but the bouncer took one look at our clothes and said, “Your clothes don’t follow the dress code for this event. You aren’t wearing a dinner jacket and bow tie, so I’m sorry you can’t go in.”

To which we replied “Your tradition is an easy one to follow, you just have to strip naked. Even when it’s really cold, women take their coats off before they go in, to show off their flesh and breasts!”

It’s very easy, but I don't follow the European tradition. But each country has its own tradition, and in one part of Africa for example, they stretch their lower lip with a plate.

Although tradition in itself is not important, here we’re talking about ceremonies that are part of the Tibetan religious tradition, which are important because we are practising the Tibetan religion and its tradition, which have been developed and upheld for more than a millennia.

The tradition of serving rice during a ceremony goes back to when Guru Rinpoche came to Tibet. The people of that time thought that as the lama was coming from India, they’d make him really happy if they served him rice. That’s how it started. Tibetans themselves eat meat and tsampa, but as Indian lamas don't eat tsampa, they thought, “What can we offer?”

“I know,” said King Trison Deutsen, “We’ll offer rice!”

And that’s how the tradition began. Tibetans didn’t eat rice for centuries, only during ceremonies. Of course now it’s different. Back then, it was really hard to get any rice to serve during monastic ceremonies, or for Losar. So whenever Tibetans came across a kilo or two, they would buy it and store it away. They’d then fill their bowls almost to the top with wheat and add a sprinkling of rice to make it look like a full bowl of rice.

When we say, “Argham” and do the mudra, we make an offering of drinking water, which is an Indian tradition. To Tibetans, to offer plain water didn’t seem appropriate. However, offering tea is a universal tradition. But no meat is offered during ceremonies, even though Tibetan food was and is predominantly meat. And rice must be offered.

Ceremonies are performed according to Dharma principles. And although ‘good’ or ‘bad’ tendrel, are just concepts, from the Tibetan point of view, to continue performing ceremonies based on dharmic principles is a good tendrel.

There are many people in the Rigpa sangha, therefore when you hold ceremonies you must perform them well. If you don't, the ceremony will descend into madness – like that ‘disco dancing’ thing you do. When you people dance, you do whatever you feel like. I’ve noticed that if someone can do a particular movement well, that’s the one they tend to repeat, again and again. What feels good to them, I realized, is what they consider to be ‘good’ dancing. They don’t follow a tradition at all. If you can shake your head well, you shake your head; if you can wave your arms up and down like this, that’s what you do. There is only one crucial point that you all attempt to follow: you must move in time with the music. If the music is fast, you move quickly; if it’s slow, you move slowly. Then whatever you do is OK. If the music suddenly speeds up and you continue to move slowly, that’s not good dancing, is it?

So, that’s that. But there’s still a lot to say. Do you understand?

To recap what I’ve said so far:

- The most important point is to be careful. You must only act once you’ve thought a task through.

- Even if you feel mentally very busy and have a lot on your mind, physically you must act slowly and move smoothly. To perform your tasks in accord with the teachings, you must do them slowly and peacefully, especially the activities carried out by lamas and monks who always do things slowly, like Trulshik Rinpoche. When Trulshik Rinpoche turns around, he always turns around slowly. Don’t be speedy! To do things slowly is the best kind of ‘conduct’ for monks and nuns; the best way of doing things.

- Ceremonies require hierarchy: a first, a second and a third level. If everyone is the same, you can’t perform a ceremony because the whole purpose of ‘ceremony’ will be lost. It’ll become like a student rally, a ‘free-for-all’ with no ceremony at all. In a ceremony, what’s done for the high participants is not done for the low ones. If what is done for Sogyal Rinpoche were also done for Philip, it’d be a terrible ceremony.

When I arrived yesterday, everyone stood up, which was a sign that you have no knowledge of Tibetan protocol. Somebody must have told you at some point that whenever a lama walks past, you should stand up, fold your hands at your heart and bow slightly. I don’t know who said it originally, but someone must have. And you continue to follow that instruction blindly. You’ve been programmed and are now just like computers! If I were the highest ranking participant in the ceremony, then of course you should stand when I walk by. If I were going to teach, for example, then you should stand up for me. But if Sogyal Rinpoche is teaching and I just come along to listen, you shouldn’t stand up for me. You only stand up for the person who holds highest rank on that particular occasion. Who that person is depends on the ceremony and the occasion. So you should think about all that when you’re organizing a ceremony. If you’ve stood up several times before the lama arrives, there’s nothing left for you to do to mark his arrival.

Even in Dharamsala these day they don’t do it properly. They do what they feel like doing, according to their own bias. So if a Nyingma lama comes in and you happen to be a Nyingmapa, you’ll stand up, while the rest of them remain seated. If Sakya Trizin walks in, the Sakyapas stand, but the others remain seated. So there’s no general rule or standard of conduct. It’s unruly, it's not good! There are no rules and there’s no discipline in Dharamsala. People from many regions and religious traditions come to Dharamsala, and as India is a democratic country, nothing can be done about it. For many ceremonies all the high lamas arrive together, Penor Rinpoche, Sakya Trizin, Ganden Tripa, etc. I, personally, stand up immediately for Penor Rinpoche, but for other lamas I don’t. What should happen is that everyone should remain seated, regardless of who enters, until Dalai Lama arrives. That’s when everyone should stand up. That's how it should be.

Basically, we’ve started copying the Gelugpas. They think that as their teacher, Ganden Tripa, is Gelugpa, then all the Gelugpas present – they are in the majority in Dharamsala – should stand up. But then all the Gelugpas remain seated when a Nyingmapa walks in. And now we do the same. When three hundred people attend a ceremony, two hundred are Gelugpas, and only one hundred are from the other schools. So, when Ganden Tripa arrives, everyone stands up. But we don't. Why should we? These Gelugpas never stand up for Sakya or Nyingma lamas, why should we stand up for their teachers? This is a very bad tradition.

During big meetings, tea and rice are served, and before we eat and drink, we say offering prayers. If the person holding the meeting is a Gelugpa, the Gelugpas chant the prayers of offering to Tsongkapa, “I offer to Tsongkapa..." (tsongkapa la chöpa bul...). If he is a Sakyapa, the Sakya prayers to the masters of the Sakya lineage are chanted. If he is a Nyingmapa, the offering prayers to Longchen Rabjam are chanted, and so on. So, while one schools’ offering prayers are chanted, everyone else remains silent. This development in the Tibetan tradition is very bad. In Lhasa everyone was Gelugpa. Now there’s a tiny scrap of democracy involved, people say many different things. The Dalai Lama himself says that it is a very bad tradition. He says that we don’t need to make offerings to specific lamas, only to Avalokiteshvara. So now everyone chants an offering prayer to Avalokiteshvara.

12. Hats

Next, when we hold a ceremony, like the one we’ve just had, it isn’t necessary for the vajra master to wear the Guru Rinpoche hat and dagam, but he should wear them for long life ceremonies, drupchens and empowerments. Why? Because during a long life ceremony, when we chant the Seven-Line Prayer and “Hung! Rise up, Padmakara...”[3]This prayer is found in the Prayer in Seven Chapters. They are the last verses of the third chapter, the ‘Prayer Requested by Khandro Yeshe Tsogyal’., we consider that the vajra master to whom we are offering has the realisation of Guru Rinpoche. That’s why he must wear Guru Rinpoche’s hat and dagam – which is very uncomfortable in this hot weather, but unique to Guru Rinpoche.

Other ceremonies require the vajra master to wear the Minling hat, with large lotus petals that unfold right and left. Every Nyingmapa lama wears that kind of hat. There are pictures of Dudjom Rinpoche wearing it, but whenever Dudjom Rinpoche was offered a long life ceremony, he would wear the Guru Rinpoche hat. During drupchens and other practices he would also wear it because it signifies that he has the realisation of Guru Rinpoche. It’s important that you know this. If he wore it for absolutely every ceremony, it wouldn't be special. Lamas only wear the Guru Rinpoche hat when they sit on a throne. They won’t even wear it when they sit in a chair. And if the hat is worn, the dagam must also be worn; they are always worn together.

In Varanasi, we held some ceremonies that were attended by followers of all four traditions, Gelug, Nyingma, Sakya and Kagyu. The plan at one point was for everyone to chant prayers of auspiciousness as four monks representing each of the four schools walked through the door. The Nyingma representative was told to wear the Guru Rinpoche hat, so I immediately objected. “This is not a Nyingma tradition, we Nyingmapas would never do this. This hat is only worn by high Nyingma lamas when they sit on a high throne, for example during empowerments. They wear it when they become the lord of the mandala. It would never be worn in a welcome ceremony!”

Someone asked me, “So what kind of hat do Nyingmapas wear?”

“The Nyingmapas have many other hats,” I replied. “There are many different kinds! Like the Rigdzin Chishu (‘General Vidyadhara Hat’) or the Minling Kuchen.”

“Oh, but if we don’t use the Guru Rinpoche hat, this ceremony won’t be so special!” said the first person.

“We want to mark the occasion,” said someone else.

“So we need a hat that’s different from ordinary hats,” another added.

“OK,” I replied. “Then the Kagyupa monk should wear the Karmapa’s Black Hat, the Gelugpa monk should wear the Dalai Lama’s yellow hat, and the Sakyapa monk should wear Sakya Trizin’s hat! My point is that this Guru Rinpoche hat is different, which is something you need to recognize. It is only worn for important ceremonies.”

Noone had anything to say after that.

13. Offering a Katak

When we make an offering to the lama, we first lay the katak along the length of the table, then put the offering on top of it, in the middle. But when we make a request, we put the katak across the width of the table in front of the lama. When insignificant people give small offerings, the lama will hang the katak around their necks. When a lama offers a katak to a high person, he won’t hang it around the person’s neck, instead he places it on their hands. You must have seen this done when we all say farewell to a lama as he leaves Lerab Ling. Lamas of the same status, like Trulshik Rinpoche and Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, don't put kataks over each others’ heads. They exchange their katas by putting them into each other’s hands. The higher of the two holds his hands above and offers his katak first, then the other holds his hands lower and offers his katak second. So when two Tibetan lamas who don’t have much education meet, you’ll see them both bending to try to get their hands lower than the lama they’re meeting. It can take ages for them actually to exchange their kataks.

Ane Sangye Chozom asked me why, after the long life ceremony I took the katak and put it across the throne.

At every ceremony, when the lama gets up, the solpön should immediately lift the dagam. You shouldn’t unfold it from below like you did yesterday, but lift it up from the top. The solpön should lift it by the shoulders, then leave it on the shrine in the shape it had been when the lama wore it as he sat on the throne. It shouldn’t be thrown carelessly all over the throne. Before the lama arrives, open the dagam and hang the fold over the side of the throne so it’s held open. At the end of the ceremony, once the Lama has left, stand it up as I’ve just described. The drung-nyer should then lay a white katak across the throne. It should be done immediately because the seat should never be empty, thereby creating the auspicious circumstances for the lama’s return.

According to the Tibetan tradition, you should also immediately tie a katak to a pillar in the temple. There are no pillars in this shrine room, but in Tibetan monasteries there are, so you should knot a katak around a pillar as a way of thanking the building. According to Tibetan tradition, this is very important. I heard Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche himself say that putting the katak on the throne so that after the lama has left his throne is not empty, is very important. Tibetans don’t like leaving anything empty. The katak must be white, which is significant because it suggests a white mind, an open mind, a clean mind; it has many meanings.

I myself have put the katak on the throne several times – in fact, at every long-life ceremony we’ve ever had. But noone here learns by watching, like Tibetans do, so I have to keep doing it myself. But it’s not my job. It’s the job of the drung-nyer, an attendant of Rinpoche, not mine.

The lama to whom the long life ceremony is offered will always need a katak to give to the lama leading the ceremony. He’ll also need another one for umze, to whom he also gives as a blessing a cord with a protection knot. His drung-nyer should put the katak and blessing cord around the umze’s neck. So the drung-nyer must make sure these things are brought to the ceremony.

If a high lama organized and lead the long life ceremony, the lama who received it should make a knot in the katak immediately, then offer the knotted katak to the organizer. So, just before the drung-nyer hands the katak to the lama who lead the ceremony, the lama who received it will tie a knot in it and hang it around the organizer’s neck. The point of this is that everyone present is witness to him tying the knot himself, rather than following the usual practice of a monk tying the knot and the lama just blowing on it. In that situation, even the Dalai Lama will tie a knot himself. And Sakya Trizin too. If they didn’t, the ceremony wouldn’t be special. But it is only done for that one lama.

If the organizer is a lay practitioner a blue scarf is offered. A yellow scarf is offered to a monk. There is also the possibility of a red scarf [but Rinpoche didn’t mention who red scarves are for]. The katak is folded in half longwise and rolled up. If the attendant puts it in his bag, it will need a cover. At the end of the ceremony, the drung-nyer takes the katak from his bag, removes the cover and gives it to the lama, who then unrolls it himself, ties the knot, blows on it, and puts it around the neck of the organizer. In the movie about the drupchen held by Sogyal Rinpoche and the Dalai Lama, I saw the Dalai Lama do that.

When the Dalai Lama participates in a ceremony, as soon as he stands up to leave, the drung-nyer immediately stands the dagam up and lays the katak across the throne. I’ve done it many times here, but no one pays attention. Today is the first time anyone has asked about it. Next year you must do it yourself. Don't forget!

Translated by Gyurmé Avertin

Edited by Janine Schulz