Bir, 2010

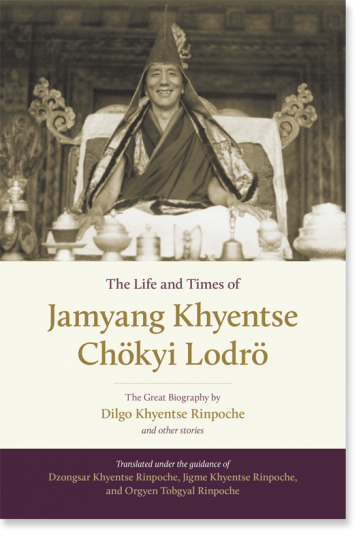

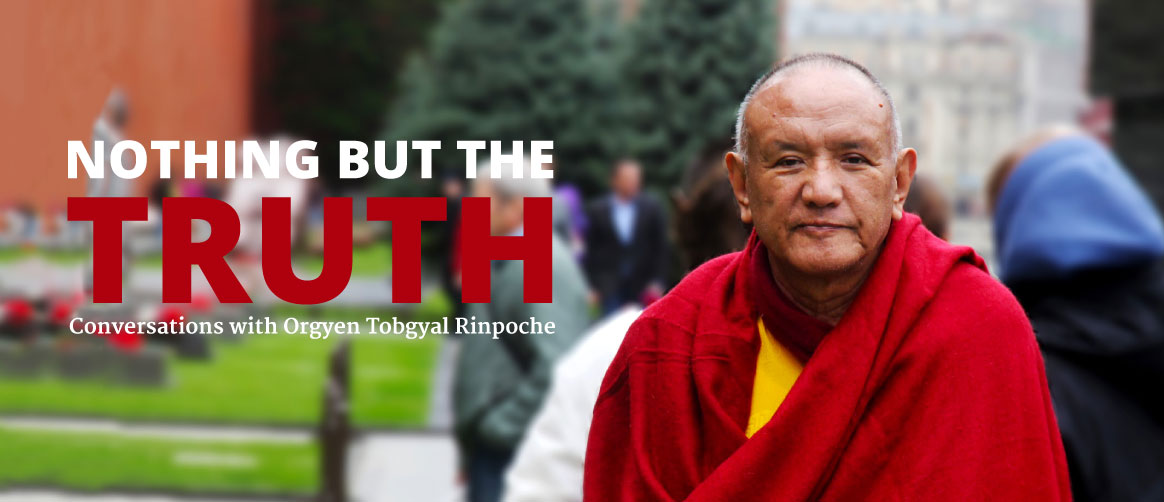

In The Life and Times of Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö, Orgyen Tobgyal Rinpoche describes how Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche burst into his house in Bir “like a whirlwind” and demanded to be told all the stories that Orgyen Tobgyal Rinpoche knew about Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö that very minute. Orgyen Tobgyal Rinpoche immediately settled himself in his big leather chair by the window and began to talk. In the end, after several such visits, Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche had recorded more than twelve hours of stories – many of us will have heard at least some of these stories before, but by no means all of them.

Why did Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche want all this information? It turned out that he was in the process of making an English translation of Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche’s majestic spiritual biography of Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö and wanted to add Orgyen Tobgyal Rinpoche’s rather more informal stories to the book. My guess is that Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche wanted to present as rounded a picture of Chökyi Lodrö as possible, to pique the interest of modern students. As Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche’s namthar tells the very inspiring and elevated story of the life and liberation of Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö, the spiritual giant, Orgyen Tobgyal Rinpoche’s stories would be to provide a more accessible foil, focussing as they do, on Chökyi Lodrö the man, as he was remembered by his close friends, attendants and family.

To whet your appetite, here is the first chapter of Orgyen Tobgyal Rinpoche’s stories describing Chökyi Lodrö’s birthplace in the ‘Badlands’ of Kham, his eccentric father and long-suffering mother – which, of course, is just the beginning of the story…

Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö’s Early Life

His Birthplace

Dilgo Khyentse told me that although we know Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö was born in the year of the snake, we cannot be certain of the exact date. I was puzzled by this and asked Dilgo Khyentse why Rinpoche’s parents, who were educated people, hadn’t kept a note of their son’s date of birth. His father, said Dilgo Khyentse, was a very great yogi, but unpredictable; he didn’t keep records of any kind. Rinpoche himself mentions in his autobiography in verse that his birthday is unknown:

Since my parents were carefree,

They kept no record

Of planets, stars, ominous dreams, and so on.

What we do know is that he was born in Rekhe, also known as Sa-ngen, the “Badlands.” To be born in Rekhe was both a good and a bad thing: good because Rekhe is one of four knots of land in eastern Tibet; and bad because it was home to many thieves, dacoits, and liars. Rinpoche always said that the people of Rekhe were unimaginably stubborn.

The walls of the Rekhe valley were so steep and difficult to negotiate that if a calf was born there, then carried out across the dangerous ravine, once it had grown up it would be unable to find its way back. Strangers, therefore, had absolutely no hope of finding their way in. And from what I’ve heard, it’s an extremely isolated and inhospitable place. Sometimes it’s said to be part of Derge, sometimes not, and many stories are told about the attempted invasions and grizzly murders that happened when the nyerpa of Jagö Tsang was young.

Yet it was in Rekhe that Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö was born, and inevitably his habits were influenced by local customs. For example, throughout his life, he loved making tea the way he drank it as a boy and always kept a brick of Rekhe tea by his treasure chest, wrapped in a black, musk deer bag that dated back to the time of Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo. He used to break off a piece of the tea brick, take it to the kitchen, grind it between two stones, mix the fine powder with a little tsampa, butter, and boiling water, churn it into a kind of gruel, then drink it down in one—often three or four cups in quick succession. Sometimes Dilgo Khyentse was invited to join him.

“This is the special tea of Sa-ngen,” Rinpoche would say. “Rekhe tea is so delicious!”

From this story, it’s clear that Rinpoche retained at least one Sa-ngen custom.

Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö’s Father

According to Gongna Tulku, Rinpoche used to say, “Masters as learnèd as my father and the Second Neten Chokling, Ngedön Drupe Dorje, who also received vast amounts of empowerments and transmissions, have not emerged among the present generation. These two great masters had similarly wild natures. They never stopped to ask, ‘Should I or shouldn’t I?’”

I asked Gongna Tulku what Rinpoche had meant by “should I or shouldn’t I?” He explained that Rinpoche’s father would do things like force his wife to offer her dzi necklaces, coral, and other precious stones to the lama (meaning himself), then sell everything off, including his tents, homes, and belongings so he could live as a homeless ascetic. “From now on,” he would say, “I want to be a wanderer without any possessions.” But at other times, he would act like a high lama and acquire many tents, a home, and all the usual trappings of wealth and position. He often appeared to crave and be enormously attached to riches and material possessions, and if thieves from Gonjo and Rekhe stole any of his animals, he wouldn’t hesitate to destroy them with black magic.

Rinpoche said, “The ultimate deity, the actual yidam of our household, Serpa Tsang, was Dudul Dorje’s Vajrakilaya. Our private protector was Zhingkyong. But it was Zhingkyong’s attendants who carried out the activities. The power of my father’s black magic was unassailable! He must have used it to kill a great many people because the inhabitants of Gonjo and Rekhe were known to live in fear of the sorcery practiced by the Serpa household.”

One day, said Rinpoche, his father would wear a long-sleeved robe; the next, a white lower robe and striped shawl; and on the third day, he would wear robes and shawls of the finest cotton. Sometimes he wore his hair long and wrapped it in a blue cloth so his head looked blue; at others, he wore a red cloth and his head looked red. But he always tucked the phurba that had belonged to Dudul Dorje into his waistband in exactly the same way Dudul Dorje had always worn it. Although rituals involving blazing tormas, and so on, are not widely practiced, Rinpoche said his father delighted in performing extremely wrathful rituals and did so repeatedly. He would throw his phurba after each of the blazing tormas he tossed, and if the torma did not turn around he would repeat the ritual the next day.

This man, Gyurme Tsewang Chokdrup, who appears as Gyurme Tsewang Gyatso in the Great Biography, son of the old Tertön of Ser and a descendant of Dudul Dorje, was Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö’s father. Gongna Tulku said he heard all this from Rinpoche’s own lips.

I asked Dilgo Khyentse if it was true that of Gyurme Tsewang Chokdrup’s two sons, it was Tersey Chime who relished wrathful activities, while Rinpoche practiced them less. He said no, it wasn’t true; Rinpoche also engaged in wrathful activity. He was never complacent about any kind of wrongdoing and would always practice a wrathful fire puja to purify even the slightest injury to Buddhadharma or the Khyentse lineage.

Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö’s Mother

I’ve heard it said that Rinpoche’s mother’s family was from Amdo and that she was a descendent of the great master Sergyi Chadral. But women are rarely spoken of in Tibetan culture, and no one I’ve talked to has been able to confirm who her parents were or even the name of her family. Yet she was a reincarnation of the dakini Shaza Khamoche. Rinpoche told Dilgo Khyentse that in the latter part of his life, long after she had passed away, she sometimes appeared to him in visions and made prophecies. But apart from Dilgo Khyentse mentioning in his Great Biography that she was endowed with all the characteristics of a dakini, no one has been able to identify with any certainty into which family she was born.

After his mother passed away, Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö asked Adzom Drukpa and many other lamas to do divinations about her next rebirth. The lamas said it looked as though she had committed a number of minor samaya transgressions and that as many Vajrasattva practices as possible should be done for her. According to Rinpoche, his mother had been a very noble being, but having endured the extreme hardship of living with a man who never ceased to behave in the most peculiar manner, it had been impossible for her to avoid breaking samaya.

Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö’s Nephew and Secretary

I asked many people about who had fathered Chakdzö Tsewang Paljor. Tashi Namgyal wasn’t sure and said, “Isn’t he the son of Rinpoche’s sister?” But it turns out that he was the son of Chökyi Lodrö’s elder brother Dudul, who was both a layperson and a tantric practitioner. It was Gongna Tulku who gave me a detailed explanation of his family lineage.

From The Life and Times of Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö by Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche.

English translation © 2017 by Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse.

Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO www.shambhala.com